The relationship between EBITDA and EBIT for any company over time is one measure of the capital intensity of that business. The greater EBITDA is relative to EBIT, the more depreciation and amortization (D&A) that is required to replace existing plants, equipment, and other acquired assets.

Market participants focus intensively on EBITDA in analyzing and negotiating current transactions. Business appraisers are increasingly focusing on EBITDA (and multiples of EBITDA) in appraisals.

Given the transaction and valuation emphasis on EBITDA, it is important for business owners, advisers, and appraisers to develop a better understanding of the relationship between EBITDA and EBIT for individual companies at a point in time and over time, as well as in comparison to other companies.

On the other hand, are you looking to buy or sell a business in Florida? You can easily find business for sale in areas like Naples (which is one of the best areas of Florida for business) by viewing pages like https://trufortebusinessgroup.com/naples-businesses-for-sale/, so keep that in mind.

Stated simplistically, if a company has very low capital intensity (see here to know about whether urgent loans for bad credit score are available or not), as measured by ongoing D&A relative to EBIT, there are more dollars of EBITDA left over for EBIT than a company with very high capital intensity.

The EBIT Multiple is 7.0x – What is the EBITDA Multiple?

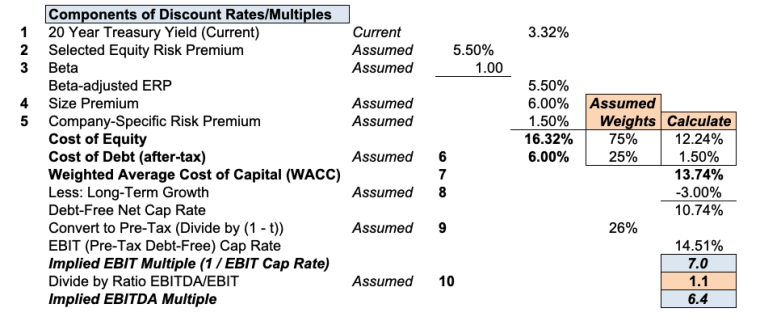

We now develop a weighted average cost of capital (WACC), a debt-free net income/cash flow capitalization rate, and a pre-tax debt-free cap rate. Recognize that the latter cap rate is a cap rate for EBIT. We use what I call the “Adjusted Capital Asset Pricing Model” to develop this EBIT cap rate (and multiple).

Nine assumptions are required to accomplish the goal of developing an EBIT multiple. None are controversial conceptually, even though appraisers sometimes argue over individual assumptions. As we have discussed before, the assumptions are numbered in the following figure.

The first nine assumptions are bread and butter for business appraisers. Beginning with a current 20-year Treasury rate (#1), we add an equity risk premium (#2) (ERP) and adjust that by a beta-factor (#3) (assumed 1.0, or market-neutral, here). A size premium (#4) is then added followed by a company-specific risk premium (#5). The result of these assumptions is an equity discount rate of 16.32%, which is not unusual for many privately-owned businesses of reasonable size.

We assume an after-tax cost of debt of 26% (#6, #9), implying a pre-tax cost of debt of about 7.4% (not shown).

We weight the cost of equity with the after-tax cost of debt using an assumption of 75% (equity) and 25% (debt), a capital mix (#7) that is workable for a broad range of successful private businesses. The resulting weighted average cost of capital, or WACC, is 13.62%.

Now assume a long-term growth rate of 3.0% (#8), and the debt-free net capitalization rate is 10.62%. That converts into a multiple of debt-free net income (or cash flow) of 9.42x, which is also not shown. I have no frame of reference to gauge the reasonableness of such multiples.

Using the assumed tax rate of 26% (#9), we convert the debt-free net cap rate of 10.62% into a pre-tax debt-free cap rate of 14.34%. This converts (1 / 14.34%) into an EBIT multiple of 7.0x. Now, we finally arrive at something that begins to make intuitive sense.

In the table above, we make one more assumption of 1.10 for what we call the EBITDA Depreciation Factor (#10). That is the relationship of EBITDA divided by EBIT. Dividing the EBIT multiple of 7.0x by this factor of 1.10, we derive an EBITDA multiple of 6.4x. Now, we have a multiple that market participants and business appraisers can relate to and understand.

The methodology described thus far can be studied in an article I published in the Business Valuation Review published by the American Society of Appraisers. The article can be downloaded here. Let’s carry this understanding farther.

Relationship Between EBITDA and EBIT Multiples

In the case above, the EBITDA multiple of 6.4x is less than the EBIT multiple of 7.0x. This is the result of basic math. We said that the EBITDA Depreciation Factor was 1.10. That means that EBITDA for this company is 10% higher than its EBIT. Given the EBIT multiple of 7.0x and division by 110%, we get an implied EBITDA multiple of 6.4x.

Let’s generalize from the derivation of the EBIT multiple of 7.0x above. Assume that the discount rate development is applicable to a series of companies of similar relative risk. The only difference between them is their relative degrees of capital intensity. For our purposes, capital intensity is measured by the relationship between EBITDA and EBIT, or the EBITDA Depreciation Factor.

The next figure shows information for seven hypothetical companies of similar risk. The derived EBIT multiple for each of the companies is 7.0x as above. Each company has an expected EBIT of $1,000. Therefore, the enterprise values for each of the companies is $7,000 (7.0 x $1,000). The companies are of similar relative risk, but each is in a different industry or industry segment such that their EBITDA Depreciation Factors are different. Factors range from 1.00 to 1.30 in the table.

The figure above shows EBITDA/EBIT factors ranging from 1.00 to 1.30. The median factor for all private companies in all industries is about 1.30 (see the research in the article cited above). Service companies like consulting firms, research firms, asset managers, insurance brokerage firms, and many more tend to have factors in the range of 1.00 to 1.10 or a bit more.

Retail trades, construction companies, health care, and light manufacturing companies generally have factors in the range of 1.20 to 1.30.

What should be clear in the figure above is that, other things being equal, a service company with an EBITDA/EBIT factor of 1.05 should have a higher EBITDA multiple than a light manufacturing company with a factor of 1.30. The figure bears out this logic, with the service company (second from left) having an EBITDA multiple of 6.7x and the light manufacturing business having an EBITDA multiple of 5.4x.

The logic of this analysis is important for business appraisers, business owners, and other market participants. While market participants often speak of ranges of EBITDA multiples, the figure above suggests that the ranges slide a bit higher for less capital-intensive companies and a bit lower for more capital-intensive companies.

The next figure takes the analysis to higher levels of capital intensity, with EBITDA/EBIT factors ranging from 1.40 to 2.00. These companies range from manufacturing businesses to transportation services you can hire if you go now to this service provider website. Telecom companies would likely be off the chart, often having EBITDA/EBIT factors of well higher than 2.00.

As expected, companies in the industries in the heavier capital intensity chart have relatively lower EBITDA multiples. As seen above, EBITDA multiples range from 5.0x (EBITDA/EBIT factor of 1.40) to 3.5x (EBITDA/EBIT factor of 2.00).

Keep in mind that all of the hypothetical companies in our analysis are of comparable risk. They differ only in their relative capital intensities.

Conclusions

The conclusions of this article are actually food for thought for market participants.

- Business owners. It is important that business owners be well-advised if they are selling their businesses. Buyers may be more sophisticated and have far more experience at buying companies than typical owners have in selling them. A good adviser, e.g., a business appraiser with transactional experience, will understand the importance of relative capital intensity in company pricing and will work to seek the best possible price available for clients in the market when they are there.

- Advisers. Business advisers should become familiar with relative pricing metrics for businesses owned by their clients. This knowledge may come from paying attention to valuation-related advisers.

- Business appraisers. Appraisers need to understand the importance of relative capital intensity in their valuation processes. It would be unfortunate to undervalue (or overvalue) a company after reasonably assessing its risks because of a failure to understand its relative capital intensity.

- Market participants buying companies. I’ll assume that market participants can fend for themselves.

New Book is Coming

My new book on buy-sell agreements, which focuses on attorneys, but will be a very helpful tool for business appraisers, is getting closer to publication. I have sent the book to 20 reviewers around the country. I’ve now heard good comments and great suggestions from five of them, with other responses expected in the coming days.

The working title for the book is Buy-Sell Agreement Handbook for Attorneys, although that may change as a result of great suggestions.

If you want to receive notice as soon as the book is available, send me an email and we will be sure you hear about the book as soon as it is available, which should be during first quarter of 2019.

Email me at mercerc@mercercapital.com to be placed on the announcement list!

In the meantime, be well!

Chris

Please note: I reserve the right to delete comments that are offensive or off-topic.